Kings without an audience -the fate of single screen cinemas of Kanpur

Kings without an audience -the fate of single screen cinemas of Kanpur

Ammar Naqvi

Kanpur, March 18

While going to a primary school in the cantonment from the city centre by rickshaw, we casually counted cinemas and tallied the film posters, trying to recognize actors and giving each other points. Fascinated by the architectural façade, counting the columns, windows, and gates, we made this our game. My parents used to tell me that children who did not behave were kept there as punishment. So, when a group of much older cousins took me to the cinema for the first time, I made a ruckus out of fear of the sound and movie playing on screen and had to be brought back home in the middle of the show.

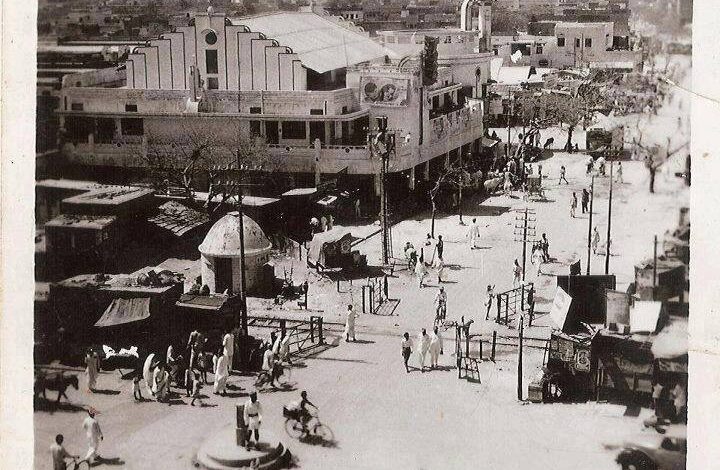

where the Manyawar showroom is now. Both were opposite PPN College, catering to young college-going adults.

The dread was so great that I went to the cinema for the second time only with friends in college. The third time I went was by bunking a class in college, with a South Indian friend, a story for some other time. It took me nearly 22 years to get that fear out and develop an interest in single-screen cinema halls, too late for them to survive. Visiting my school last year, I counted only two single screens running the show out of ten, three of its buildings couldn’t survive.

Cinema was also part of daily conversation, a collective memory in the household. I vividly remember my mother telling her story of going to the cinema. It was an all-women outing to watch the 1982 film ‘Nikah’, planned by older women of the house, with strictly no men allowed. ‘Since we haven’t watched our own Nikah, we will watch in the theatre’ was the convincing statement made to keep the men out. Many other women from the locality joined in, hoping to see how a ‘Nikah’ is done on the silver screen, but in reality, escaping the daily drudgery. It was a large group. A photo op missed.

immigrant to the city, built in the year 1946 (Source: Wikimedia).

When looked deeper, Kanpur, an industrial city had nearly 37+ cinema halls running at its peak. These buildings, with the blend of Art Deco, Modernist, Brutalist and Minimalist styles, were the welcome architectural addition to the city’s landscape, a soothing visual to the eyes, worth preserving.

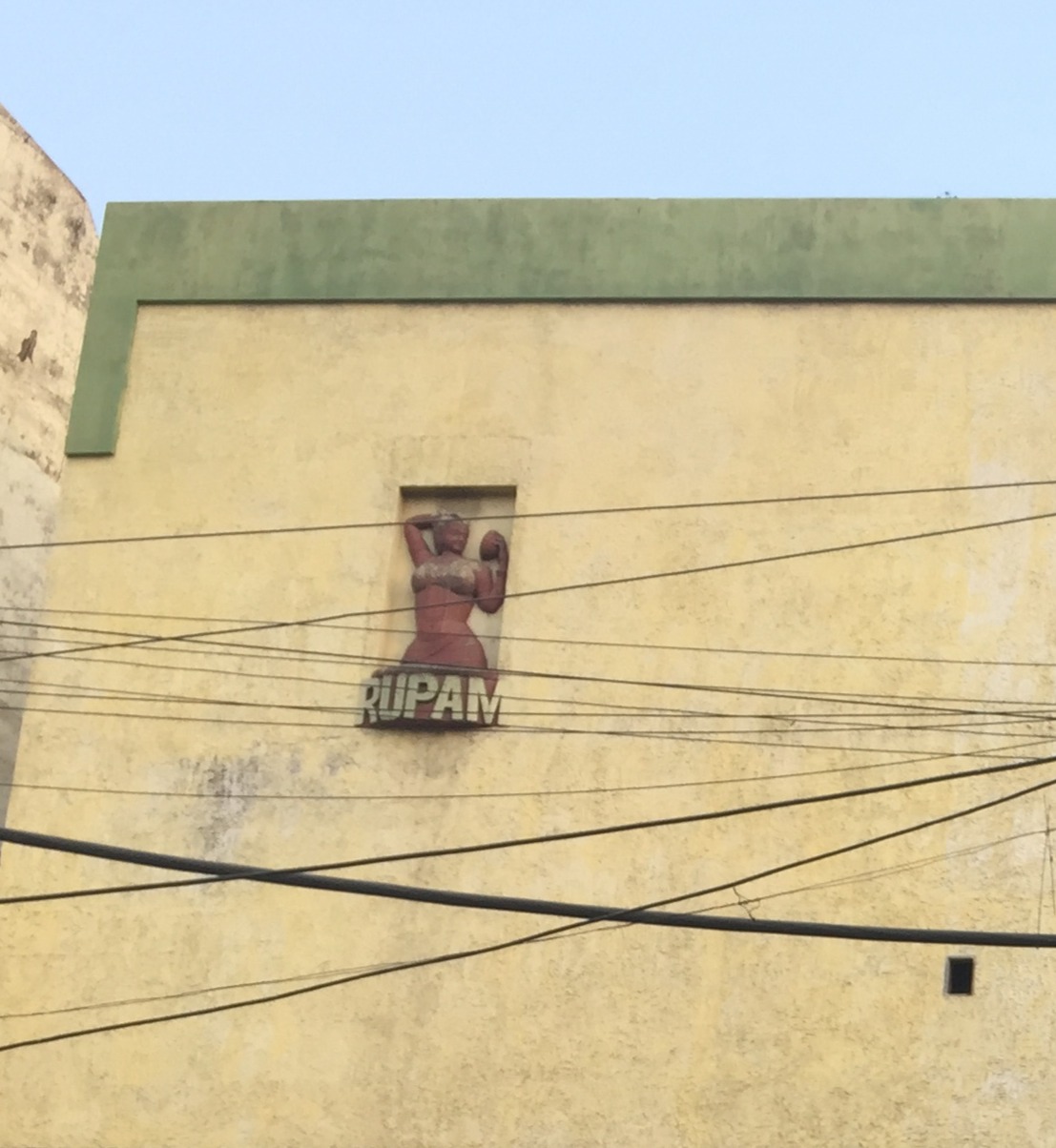

housing units, including one for its former caretaker. Located in a bustling market P Road, designed for blue-

collar workers and the working class, it stands as a prominent landmark.

The journey of India’s single-screen Cinema began in 1907 with Elphinstone Picture Palace, which was later renamed Chapin Cinema in Calcutta and built by Jamshedji Framji Madan. The ‘Pearl Theatre’, later known as ‘Kohinoor’ Theatre and then Royal Theatre, was constructed on Gwynne Road in Aminabad, Lucknow, in 1911, and is considered the first theatre of Uttar Pradesh.

here in a white shirt), it has been showing films continuously since then, except for two nine-month hiatuses

due to the Covid pandemic and legal issues.

To understand the History of Cinema Screens in Kanpur, one has to understand the history of labour movements and the composition of settlements. Settlements in Kanpur developed around the mills and factories. These were the formal colonies of workers directly working in factories like Alen Gunj for TAFCO (A shoe-making factory) and mohallas (locality) of informal workers working in ancillary industries like Gwaltoli, situated behind Elgin Mill. From pre-independence, Kanpur has been a cosmopolitan city. The Bengali working class, the Punjabi settled around Govind Nagar, Gumti, and Harjinder Nagar, the Kahtris settled in Krishan Nagar (Jugal Palace), and Shaym Nagar. Within these localities came the need for cinema catering to a wider audience.

sellers of clothing, such as Oswal, set up stalls here. This is situated opposite Christ Church College, built in

1866.

Localities also developed according to caste occupations: Chipiana (for wearers and printers), Kanghi Mohal (occupants who made combs of wood and bones), and Chudi Mohal (inhabited by the Manihar caste who made bangles). The physical location of the Cinema was a determining factor to the gentry it catered. Thus, Delite, located in the cantonment, caters to residents of the Cantonment and areas around ‘Faithful Gunj.’ The now-demolished Manjushree at Ghantaghar was meant for passengers staying in lodges and blue-collar workers.

At the beginning of Mall Road, towards the Cantonment side, is located one of the oldest cinemas of Kanpur, Regal. It was the only English Theatre showing English films to the resident British, with chairs made of bamboo and woven with jute and cushioned, famous for the Poshest Gentry, mostly English and later white collar Indian working calls. The Mall Road around this was a nostalgia recreated in a far of land. This was also known as ‘Thandi Sadak’ – The Cold Road locally, in colonial times (Just around Mari Company Flyover- a distorted version of Murray and Co.) with water sprinkled, Billiard rooms, Restaurants like Quality and Volga, and the Valerius Hotel Around, according to Vivek Gupta, one of the owners. The last film screened was in 2006.

Nishat Cinema, noted for its modest minimalist design, is situated on the aforementioned Mall Road. Seasonal sellers of clothing, such as Oswal, set up stalls here. This is situated opposite Christ Church College, built in 1866.

The Gumti area had three prominent Cinema Halls, the earliest being The New Basant, The Jai Hind Cinema, and the Himachal Cinema, all made in the post-partition era, with new settlers coming in, with a spirit of building the nation. These were apart from business a community enterprise, in the selection of movie screening and running of shows. The Jai Hind Cinema was built around 1950, according to confectionary shop owners, Narendra Kumar and Raj Kumar. This was originally owned by Lallu Mal Gaya Prasad and leased to Ganesh Babu Verma, who later owned Poonam Talkies.

Conditioner in Kanpur, according to its employees. With two shows a day, and only Big Pictures and festive runs

to do business the hall, partly functions as Party Hall to make ends meet.

The early demise of the cinema began with the coming of Television, DVDs and subscriber-based cable-operated systems. The death knell came with Multiplexes. It was not just the viewership experience that changed, but the process of Movie distribution too. While earlier producers gave distributors reels and rights of films for 10 years, it first came down to three years and then to three months to be sold off to OTT Platforms, for higher prices according to the owner of Deoki Palace, Mr Yashpal Sharma, which gives cinema shorter window to make profit. The number, according to former Cinematographer Hemant Kumar, nearly 25,000 single screens in the 1990s the single screens are reduced to around 6,000.

By the 21 st Century, movie-going and screening experience became capitalist in its orientation. The physical prints shipped to theatres have been replaced by digital distribution. The 800-900-strong distribution network of Chandni Chawk was wiped out. With this, the viewership experience changed from personal, intimate, and community experience to transactional, moneyed, service-oriented leisure.

With big production houses like Dharma Productions, Yash Raj Films, Amir Khan Films and others directly taking over distribution and the coming up of Multiplex Chains, like PVR (1990), Cinepolis (2001) and INOX (2002) upgrading the screens, technology in sound and movie projection with huge capital involved, Single Screen cinemas couldn’t compete in an age with alternative sources of entertainment, like OTT and electronic media, which reduced the footfall to keep the business going. Some survived by turning Single screens into Multiplex, with a tie-up with Multiplex chains, as Heer Palace and Ajay Devgan owned NY Cinemas. Some turned entirely to marriage halls.

favourite of Manoj Kumar, who wanted to have this kind of theatre in Mumbai, during the premiere of the 1967

film Upkar. (Curtsy: Wikimedia).

During my research, the stories of two cinema owners and the rich history of their halls left a deep impact on me, which gave me a perspective to look at single-screen theatre beyond business equations of profit and loss, into carrying forward the legacy. In my detailed interaction with Yashpal Sharma, the current owner of Deoki Palace, I came across operational difficulties, changes in production and procurement procedures, and much inside information about running a single-screen hall. Operationally, the cinema took a hit with the COVID-19 pandemic, with a decline of families of four coming as audiences and later Metro construction closing the main gate, leaving a tough navigational route to enter, the increase in license fees, and high tariffs and taxes.

comfortably with a public that craved entertainment.

The Palace was built by his father Surendra Nath Sharma, and he put his hands in details of construction while studying in class 11 th . The meeting soon turned emotionally charged, of how the cinema had seen the heydays with more than 1,400 people waiting for the exit of the same number of people, a separate window of tickets at the cycle stands, wait for Saturday for brisk business, and how social position diminished with declining business, running the cinema in absolute loss.

with a capacity of 1,409 seats and an 80-foot-wide screen. Notice the very futuristic-looking façade, with a

mix of tiles and glass, which gives a sense of a mixture of Brutalist and modern architectural styles. (Any

input on identifying the architectural style is welcome and will be updated).

There has been an effort by the Uttar Pradesh government under the ‘Integrated Incentive Scheme’ to revive the single-screen cinema, partly converting them into a shopping mall with smaller theatres, but as Yashpal Sharma pointed out, constructing within the structure without completely demolishing is an architecturally impossible task, pointing to policy and ground reality mismatch. What it leaves out, that leads to the hesitation of upgradation is an absence of addressing the fundamental issue of securing films and the need for blockbusters to stay afloat.

camera).

Yashpal Sharma, the owner of Deoki Palace at his office, with his friend Yugal Shrivastav (behind the camera).

But perhaps the most interesting Cinema Hall of all is Himachal, located in Gumti No.5. this is what one would call a people’s theatre with its roots in the community, as it operated. Named after his father Himachal Singh Tomar, Kunwar Shankar Singh Tomar inaugurated this in the year 1964, with the first movie being screened was Godan starring Raj Kapur.

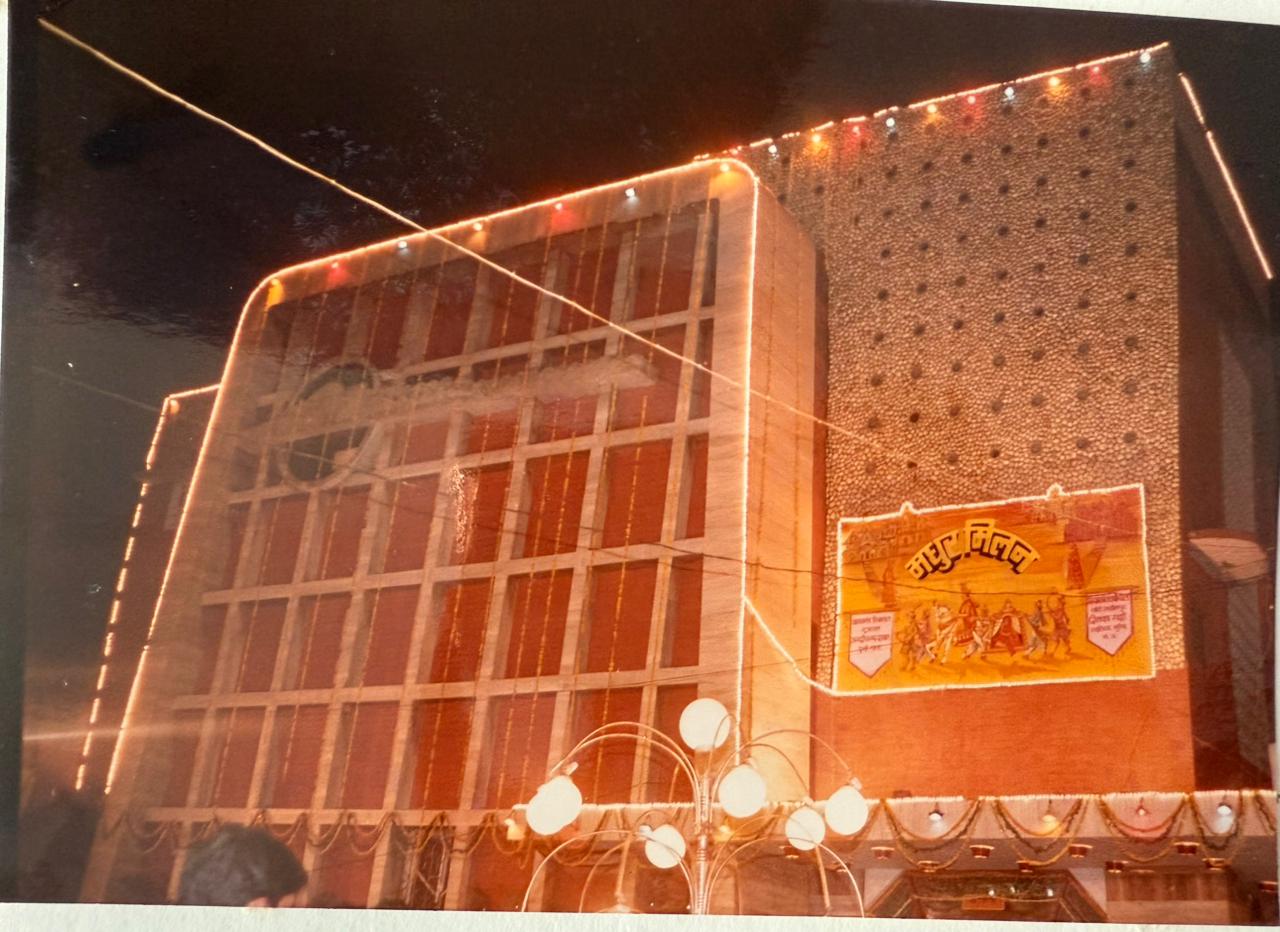

Class. Madhur Milan move is being screened in the photo. (Curtsy: Karan Tomar)

The old building of Himachal Theatre. The seating capacity was 800, with a Balcony, Family, and First Class. Madhur Milan move is being screened in the photo. (Curtsy: Karan Tomar)

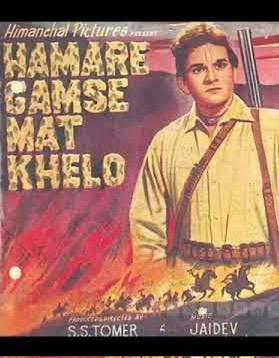

The story, according to local lore, is that Shankar Singh Tomar had the desire to act in films with a talent well recognized, but having a tiff with actor Pran, he directed the film Hamare Gam Se Mat Khelo (Don’t play with our sorrow) in 1967, under the banner of Himachal Pictures, with music given by Jaidev and shooting done in Kanpur and Mumbai. Many of the characters in the film were locals who acted, with this Shankar Singh brought the cinema to the community he resided in, a fact till now much cherished. On election days, the movie was shown free to the voters.

The poster of Hamare Gam Se Mat Khelo was Directed by Shankar Singh Tomar.

In the year 2019, the Himachal Cinema was reopened with a shopping complex and Cinema, by his grandchild Karan Singh Tomar, thus continuing the legacy. Gone are those slow-moving rickshaws, with their hooded cover, the leisure child had to observe and create games out of the blue (with cell phone sticking out as extra limbs), and those single-screen Cinemas, with attractive facades, inciting, ever inviting. Cinemas now are hidden boxes, inside hideous glass malls, mechanical capitalist entertainment service providers with ratings, devoid of a human element. Earlier, single-screen cinemas allowed food and beverages from homes, with elaborate family plans made in budget-friendly pockets. They represented a character of the city, catering to the working class or service class gentry. These cinema halls were deeply embedded in nations’ history and imagination’ not just in films but their very existence. The Jai Hind and Gopal Talkies were the symbol of the nation born anew, Himachal was a cautious start with its iconic film production as an effort to find and look for community identity after the China debacle and Deoki the resurgent with confidence. Architecturally speaking, these cinemas have come a long way, from the very Indian-looking Art Deco of Dwarka Palace, the experimental design of Dekoi to modernist Satyam. They were owned, managed and profited locally, giving shape to working-class skilled around filming. And it is perhaps this absence of big capital, that gave me a very welcoming and warm response from nearly all the owners of single-screen cinema.

(Note: A special thanks to the owner of Deoki, Yashpal Sharma with whom I had a long conversation over many aspects of running the cinema and the owner of Himachal Cinema, for his prompt and enthusiastic support, understanding the importance of bringing his legacy to the public domain).

(Ammar Naqvi is an independent translator, researcher and academic writer, who has worked with Azim Premji University and other regional publishers in different capacities. Currently , he is associated with Doon Library and Research Centre, in public discussion on Regional Literature in English Translation.)