42 BRO labourers buried in snow avalanche, 15 rescued, in Chamoli district

42 BRO labourers buried in snow avalanche, 15 rescued, in Chamoli district

S.M.A. KAZMI

Dehradun, Feb 28

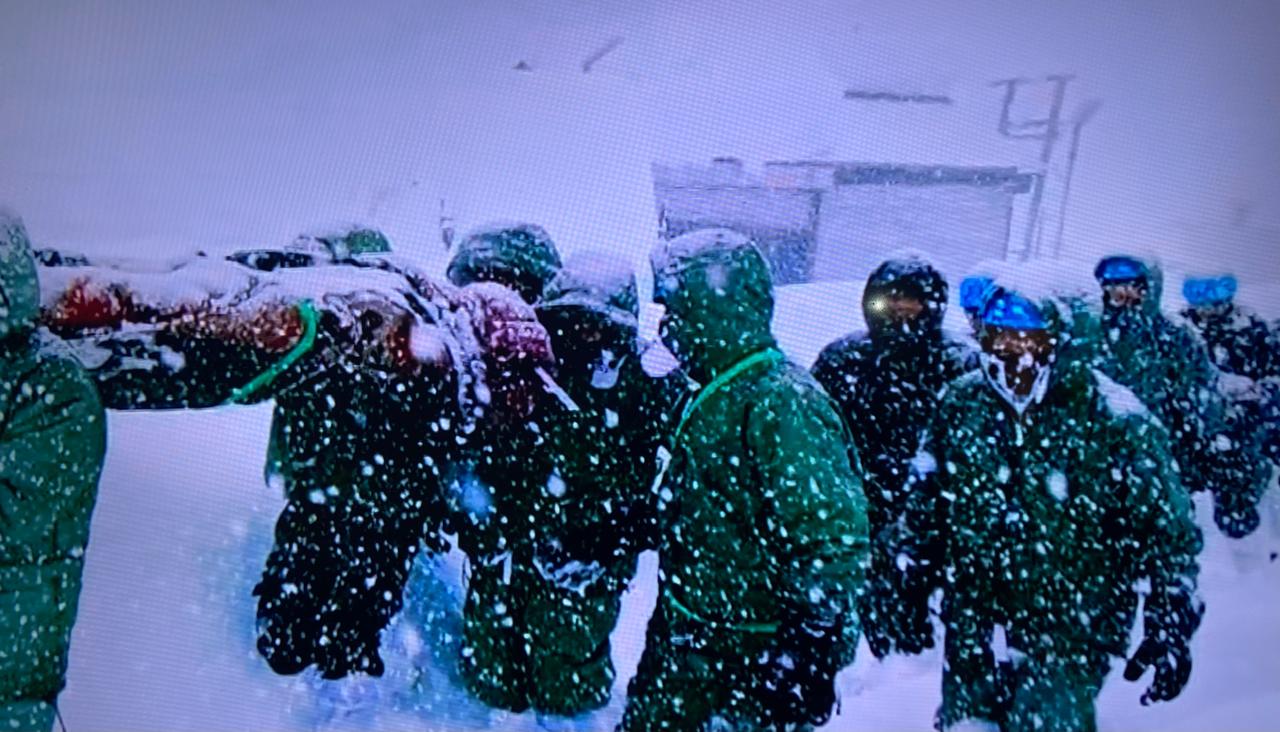

Tragedy struck road construction workers of Border Roads Organisation (BRO) when 57 of them working on a road project between Mana village and Mana pass in Chamoli district of Uttarakhand were buried in a snow avalanche following breaking of a glacier in the area, today.According to BRO and state government officials 15 of these labourers have been rescued and admitted to hospital at Mana village. A team of State Disaster Relief Force (SDRF) has been sent to the spot from nearest Joshimath post. High altitude rescue teams have also been prepared at Gauchar and Sahasradhara, helipad for rescue operations.

Uttarakhand Secretary Disaster Management Vinod Suman has said that 57 workers got buried after the snow fell. However, 15 have been rescued. Ridhim Aggarwal, Inspector General of Police, SDRF, a total of 57 workers of Border Road Organization (BRO) were buried in the avalanche incident near Mana village, District Chamoli.

According to Commandant BRO, 42 labourers are still missing. A team of SDRF has left from Joshimath but due to intermittent rains and snowfall road has been blocked at Lambagad, and even army officials are being contacted for help in the rescue operations. SDRF and district administration are coordinating with BRO and Army officials to coordinate the operations. As soon as the weather conditions improve, the high-altitude rescue team of SDRF will be landed at the nearest available place by helicopter, officials said.

Uttarakhand Chief Minister, Pushkar Singh Dhami who is monitoring the rescue operations said, “Relief and rescue operations are being conducted by ITBP, BRO and other rescue teams. I pray to Lord Badri Vishal for the safety of all the labourer brothers.”