Making sense out of wildlife journey of Independent India

Interview with Forester- Environmentalist and Author Manoj Mishra

Making sense out of wildlife journey of Independent India

Interview with Forester- Environmentalist and Author Manoj Mishra

Rashme Sehgal

Dehradun , Oct 7

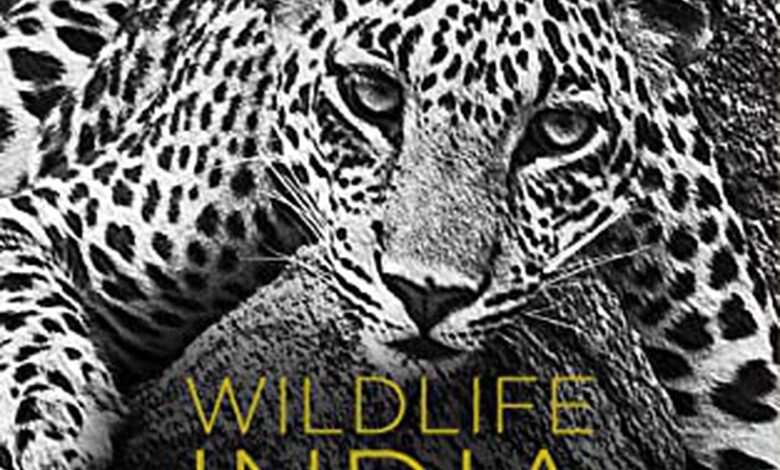

Forester Manoj Mishra, a founder member of the ‘Yamuna Jiyo Abhiyaan’, has come up with a brilliant book titled ‘Wildlife India 50’ to commemorate 50 years of the enactment of the Wildlife Protection Act 1972. Mishra has edited a collection of excellent essays that provide vignettes by foresters ( members of the Indian Forest Service) on some of the initiatives taken to protect wildlife in these 50 years as also tried to analyse reasons for the failures of some of these initiatives. Seldom has a book captured the hard work and commitment shown by our foresters who work night and day to protect this irreplaceable legacy. Senior, journalist, author and poet Rashme Sehgal interviews him.

Q. Leading conservationist HS Panwar who has been the founder-director of the Kanha Tiger Reserve, the first director of the key Project Tiger initiative and also founder –director of the Wildlife Institute of India in his essay made the observation in your book that animals whether predators or those predated upon need inviolate spaces otherwise wildlife cannot survive. How far do you agree with this contention especially since space remains the biggest constraint in India?

A. A secure and appropriate home is necessary for the well being of any living being. His chapter brings out very lucidly how this rule applies equally to all large mammals though Panwar has chosen to focus on the ‘Barasingha’ and the Tiger. The author very lucidly emphasizes how it was the lack of suitable habitat and not predation that was responsible for the ‘Barasingha’ in Kanha National Park inching towards extinction. The process was reversed and the species saved once a suitable habitat was restored.

On the whole debate of inviolate spaces, all I can say is that in those early days which Panwar Saheb alludes to, the thinking was that inviolate spaces were required for conservation

Q. How much has the Scheduled Tribe and Other Traditional Forest Act ( FRA 2006 ) law tied the hands of the average IFS officer. Several allusions are made to this indirectly in your book?

A. It is not really the FRA 2006 law itself but its motivated implementation dictated not by the facts on the ground but by extraneous considerations including political interference that is the real problem.

Q. Arvind Kumar Jha, an Indian Forest Service(IFS) officer who also worked in the areas of tribal development and water conservation writes about how in 1990 when he was working in Gadchiroli, a Collector and Assistant Collector were stopped by IFS officials for trying to smuggle a tiger skin to Mumbai where they could sell at a good price. The state Home Secretary sympathized with Jha and the two IAS officers were strongly rebuked. Seventeen years later, the forensic report that had found evidence against the two IAS officials has disappeared. Would IFS officers have the guts to take action against IAS officials today given how strong their lobby is and given that a large number of IAS officials seem to enjoy political support?

A. In an ideal world the law does not and should not recognize the position exalted or otherwise of an alleged offender. But in the real world often people with position, contacts or influence do get away with murder (sometimes literally). But it is wrong to paint it as the outcome of this versus that lobby. There have always been people like Arvind Jha (in this case) who have endeavoured to uphold the law no matter what and hopefully there will be many like him in the present and in the future.

Q. Two conservationists Ghazala Shahabuddin and Anjali Bhertari focus on how several initiatives to promote ecotourism or nature tourism in the state of Uttarakhand have failed. Their reference is to cite one example of how the Pawalgarh village located next to Corbett tiger Reserve was declared a conservation reserve in December 2012 but this initiative has not been operationalised to this day. Your comments.

A. Introduction of Community and Conservation Reserves (CRs), as protected area categories in addition to existing sanctuary and national park, in the WLPA vide its amendment in 2002 was a very welcome step. So was promotion to ecotourism in them. Unfortunately these two Protected Area categories despite their declarations have failed to take off.

The key issue here pertains to the rules framed to implement them and the failure to revise them when it seemed they were not delivering.

Moreover as is obliquely referred to in this chapter is the fact that with change of guard in form of a new officer in charge of a PA sometimes priorities change and the new person might not be equally enthused about promotion of certain activities that were the norm previously. The result is the sudden cessation of some innovative initiatives that were delivering.

This chapter highlights an urgent need to evaluate how CRs are doing and what course correction is required if they have to deliver in the spirit in which they were created.

Q. A special focus has been the rise of smuggling of rare species of birds and animals during the past decade. Global analysis has placed India on top ten countries where airlines are used for trafficking prohibited wildlife products. More shocking the book refers to how via internet, 24,267 birds belonging to 43 species of birds whose sale has been prohibited were found to have been sold. Your comments on why this is happening.

A. Smuggling of tradeable goods as a low risk and high returns activities is age old. Illegal trade in wildlife and its parts and products is one such unfortunate fact which has adversely impacted our fast dwindling biodiversity reserves. The Convention on International Trade in endangered species of wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in 1975 was global response to this emerging threat. But despite best efforts there is little respite on illegal trade in wildlife made worse by a “click of a button” which has made enforcement of laws doubly difficult. This chapter highlights well this dilemma.

Q. Wildlife biologist Faiyaz Ahmed wrote an excellent piece on how Kuno National Park had been selected as a second home for the Asiatic lion with villagers of 24 villages inside the park being relocated for this purpose. The villagers now complain once they heard that the Kuno park would be used to introduce the cheetah that they have been misled. Your comments.

A. In a politically charged atmosphere where decisions are taken more at political merit than otherwise, Kuno and the fact that it awaits lions for more than two decades now is a sad tale. This chapter has captured the story of local people made sacrifices for the advent of the lions which never came, despite a Supreme Court order.

Q. One of the most poignant chapters was R. Srinivasan Murthy’s piece on the re-introduction of tigers in the Panna Tiger Reserve where in 2009 not a single tiger could be found. It was only when T-3, a male tiger was brought and he decided to talk 200 kilometres to return to his old habitat which in turn caught the attention of the nation that Panna gradually began to return to track. In 2015, it boasted of 34 tigers. The bifurcation of this reserve with the setting up of a dam in Daudha has created a tremendous sense of loss with the IFS watching these developments helplessly. Your comments.

A. Yes, Murthy has narrated the story of return of tigers to Panna in a captivating manner. And why not, since he led the effort in a true spirit of dedication and unprecedented leadership. Plans to construct a high dam at Daudhan in the very heart of Panna Tiger Reserve goes against this crucial Wildlife Protection Act (WLPA) which this present government has been trying to dilute. It also has the potential to undo all the good work of Team Panna. May better sense prevail and their destructive plans not materialize.

Q. The insensitivity shown towards wildlife is reflected both in the policies of both the state and central government. To cite an example is how the Tamil Nadu state government wants to set up a coal thermal plant in the sensitive Gulf of Munnar National Park set up to save marine ecology. Your comments.

- A. The story of Gulf of Munnar Marine National Park in the book is one of my personal favourites. Such a move would be a disaster both for marine biodiversity and the local fisherwomen and men if the developmental plans like a thermal power plant there were to go forward. But the chapter is much more than just this because it describes the lives of these couragesous fisherwomen who dive deep into the ocean bed to fetch sea weeds.

Q. Your book highlights how the Great Indian Bustard can be saved if the government agreed to invest in underground high energy transmission lines which they have not done. Why is that?

A. Great Indian Bustard (GIB) and its future shall determine if we as a nation delivers or fails to in the next 50 years on the wildlife conservation front.

Conservationist Sumit Dookia writes about how ensuring a secure habitat in the Desert National Park (the only remaining GIB breeding population in the country) is far more important than successfully breeding the bird in captive conditions presently underway with timelines running into decades.

Ensuring underground high voltage transmission lines from the solar and wind farms in the Desert is one of the strategies for securing the habitat. It has also been mandated by the Supreme Court of India.

Q. Forester Rabindra K. Singh describes the almost quixotic situation when eleven elephants referred to as Ashok Dal enter a mission school in Surjuta district in Chattisgarh in 2016 and how the forest department along with the local police managed to diffuse the situation. But man elephant conflict is on the rise because of habitat loss of elephants. How can this situation be reversed.

- A. Rising Man-animal conflict scenarios, aptly described by RK Singh via the story of wild elephants entering a major city (Ambikapur in north Chattisgarh) is the greatest real-time and futuristic challenge facing the wildlife establishment in the country. The law needs to rise to this challenge which if not addressed appropriately can put to naught all past efforts made on the wildlife conservation front in the country where rising human numbers and wildlife species including wild elephants are bound to clash.

Q. Why is the Modi government constantly promoting a line of thinking in which environment protection is a major hindrance to economic progress. Why have conservationists not joined hands to dispel this.

A. It is not just the current political dispensation but even those before it (with perhaps the sole exception of Indira Gandhi era) that have looked at conservation of wildlife with suspicion and as a threat to economic growth. They regard wildlife conservationists as elitist in mindset and approach and in extreme cases even dub them as anti-nationals. This must change especially in today’s day and time when the scourge of climate change brought about by human’s mindless exploitation of nature in the name of economic growth poses an existential threat to the human species as well. Let us not forget that economic growth stands on ecological well being and not the vice versa. There is no Planet B for humans to migrate to, not at least in the foreseeable future, by which time it might be too late for all of us humans included.

—————————————

Rashme Sehgal is an author and senior independent journalist who has worked in several leading papers including the Times of India, The Telegraph, The Independent and The Asian Age.